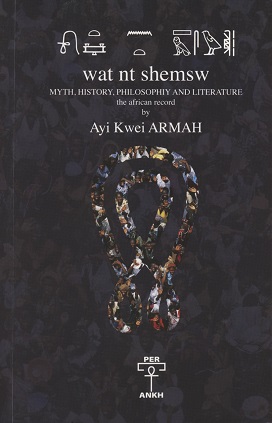

I have recently been reading Ayi Kwei Armah’s book The Way of Companions. It is a fascinating book that I think teaches us all something about some key ideas that should receive further emphasis in contemporary African culture, thinking and being. This book is ultimately about education, and in particular about African education. From page one, Ayi Kwei Armah stresses that the European academy disenfranchises the existence of African history, culture, knowledge. The Hegelian phrase “Africa has no history” is used in his writing. There is a purpose to this. This disenfranchisement, done on a large scale, ensures that African minds will remain fixed on supporting the European world view, at the expense of the African one. In the sections to come, I shall go into a bit more detail about the origin of this disenfranchisement and how it has been installed in Africa, in Ayi Kwei Armah’s book The Way of Companions.

Outside influences on Africa

Africa has historically not been an insular society. There have been other societies bordering Africa whose influence has been felt on the continent. The Assyrians, the Hittites, the Persians, the Ancient Greeks, the Romans, the Hindu, the Malayo-Polynesians, the Arabs, and Europeans in most recent times have all influenced Africa in one way or another. Of these societies and their influences, not all have come in the name of peace and mutual prosperity. There are those societies over the historical period of Africa’s existence that ultimately emerged as conquerors even if their initial overtures indicated otherwise. These societies that have conquered parts of Africa have been those whose cultures are such that in order for them to live, their conquered foes had to ‘die’. This is what is known as a zero-sum game. A zero-sum game is one that promotes a win-lose scenario and that eschews a win-win or a “live and let live” scenario. Or, “mine is good, yours is not good”. In a zero-sum game, for the winner to win, there must be a loser. In particular, Ayi Kwei Armah accuses European and Arabian conquering ways of this zero-sum orientation, without using the term zero-sum (that part is my emphasis). Why then would we expect these societies (Arab and especially European) to teach African history and the conquered African people in ways that are true to those Africans. They won’t.

Understanding and explaining Africa’s struggle with colonists

In order to set the record straight, Ayi Kwei Armah in The Way of Companions has embarked on some “next level” sankofa, an Akan phrase that means “go back and retrieve”, digging into the far past, to the deep well of culture, knowledge and wisdom of the people and time of pre-dynastic Kemet (Ancient Egypt). Dynastic Kemet brought the system of hierarchical rule over the entire land, the concept of empire, embodied in Narmer’s rule of both lower and upper Egypt. Prior to that, there were millennia of rule during the pre-dynastic time, when a more egalitarian culture persisted. Ayi Kwei Armah draws our attention to an earlier system of social ordering that existed among smaller communities of the pre-dynastic time, rule based on egalitarianism rather than on the hegemonic domination of a minority privileged elite. The dynastic form of rule emerged and overtook the egalitarian forms of the pre-dynastic era during and after the time of Narmer, the first ruler of the first dynasty. Ayi Kwei Armah argues that the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato adopted the hierarchical form of rule by an elite as the ideal form of government after studying the Kemetic version. Plato’s writings in turn influenced Roman and later European forms of government, where an elite rule through domination and violence. The early fathers of post-colonial Africa and the West Indies, Ras Madonna (West Indies), George Padmore (West Indies), Jomo Kenyatta (East Africa), Peter Abrahams (South Africa) and Kwame Nkrumah (West Africa), who met in Europe to decide Africa’s fate, showing that they were not clued up on Africa’s ancient past (i.e., they did not demonstrate any knowledge in their speeches and writings for instance about Africa’s greatness during Kemetic and Nubian times, my emphasis) then chose Plato’s European model of government as the model to replace the colonial one. In essence, a European elite was replaced by an African one.

In other words, Ayi Kwei Armah lets us know that although the political fathers of Africa were pan-Africanists, their ideas of government constituted a repackaging of the European model that was extant in colonialism. More than that, he also argues that these founding fathers lacked the intellectual training in Africa’s creative and historical resources from which they could have drawn inspiration during the fight for independence in those days of the fall of European colonialism.

Understanding African Education as a way of understanding Africa’s plight

Ayi Kwei Armah argues that to set Africa on its true path, we need to harken back to the egalitarian ways of the culture of pre-dynastic times. In this book, Ayi Kwei Armah outlines what this way is, its theory and its function. A crucial point Ayi Kwei Armah makes is that in pre-dynastic Kemet, there were two broad shemsw. What is “shemsw”? Well, it is a term, says Ayi Kwei Armah, that in the language of Ancient Kemet means “companions”. Ayi Kwei Armah explains this term as meaning something of a group, a close cadre of individuals, who constitute something of a family. He distinguishes the blood family (wahyt) from the intellectual family (shemsw) and he describes the latter as “[designating] a group that came together in order to undertake a common journey”. In this book, he speaks of two shemsw groups. The first group, shemsw Maât, are what Ayi Kwei Armah calls the “cooperative egalitarians”. As the name implies, they are the ones who value equality in their interactions. The second group, the shemsw Seth, are those “believers in the great efficacy of violence, unequal organization as a guarantee of the good life”. Basically, the Shemsw Maât employ persuasion and truth through argument and negotiation to exert influence. The Shemsw Seth on the other hand employ force through violence and guile through deceptive strategies as their ways to exert influence. These descriptions position the Shemsw Maât as the philosophers, philosopher-kings and the sages, and the Shemsw Seth as the aristocrats, the politicians, the warriors and the warrior-kings. The latter rule through a hierarchical elite, at the top of which is an absolute ruler.

As a related point, I find this dichotomy between the Shemsw Maât and their counterparts the Shemsw Seth to be a really interesting distinction that can be applied to the two main political systems of organization in West Africa and among the Bantu groups of central and Southern Africa. The Shemsw Maât originated with sisters (Aset/Isis, Nebet-Hut/Nephtys and their group in Kemet, which included Asar/Osiris and Jehwty/Thoth), while the Shemsw Seth originated with brothers (Šeteš/Seth, Her-Râ/Horus the Elder, and others who foregrounded the warrior path to leadership). In sub-Saharan Africa, where we can take West Africa as an example, these two forms of traditional government are still extant. We have on one hand those communities led by a philosopher-king or sage, such as you would find among certain peoples of Northern Ghana and Burkina Faso that have a ‘tendana’ or a priest of the Earth shrine, who serves as leader of the community. These communities (e.g., the Dagara, the Konkomba and the Sissala) are led by the equivalent of a council of elders with the tendana as their leader and is in stark contrast with other people of West Africa who have been led by kings and emperors.

The Akan system of rule appears to be hierarchical, in the sense that within each group, there was traditionally a ruler who was seen as a king under whom were chiefs of various divisions, and these chiefs also led (still lead) sub chiefs. Elsewhere in West Africa and beyond, there are groups such as the Baganda, the Dahomey, the Igbo, the Mande, the Mossi, the Yoruba and the Zulu (as a few examples) mostly incorporate the hierarchical rule format. Also, there are African communities outside of West Africa that are led by a community of elders, in decentralized communities. One group are the Tonga-ila people that the late Zulu shaman Credo Mutwa said he learned some deep esoteric knowledge from. I find that these communities whose forms of government and social orientation we can say follows the Shemsw Maât format seem to also in general incorporate spiritual education and spiritual practices more broadly within their culture. In West Africa, these people have some of the most powerful systems and heritages and bodies of spiritual knowledge.

Education to empower, not to disenfranchise and to oppress

Importantly, Ayi Kwei Armah argues that it is through the education systems bequeathed to Africans during colonial times that systems of European dominance have been preserved and propagated in Africa. The education systems installed in Africa by the European colonizers were not set up to empower Africans to look out for African interests and advancement. Quite the opposite. Instead, he argues that they were set up to create an African elite trained to revere and promote European thinking, mindset and values while simultaneously rejecting African thinking, mindset and values. It should come as no surprise then, that when African leaders born of this form of “European mental colonization” (through the education they received) subsequently assumed positions of power in business, in politics or in society, they then drew their ideas, their inspiration and their policies from ways of thinking that foregrounded and celebrated European-leaning thinking, mindset and values while backgrounding and deemphasizing the same for the African case. The notion inculcated in the minds of much of the African elite educated in the European colonial way was that Africa has little to nothing of value from its past to offer as inspiration for the development of contemporary African society. Contemporary African people should therefore aspire to European standards, values, and ways. This, in Ayi Kwei Armah’s view, contrasts with the history of thousands of years of education in Africa, at least during pre-dynastic Kemetic times, that had the Shemsw Maât system in place, and through which pre-dynastic Kemetic society flourished. The Shemsw Maât egalitarian approach was enshrined in the educational system known as per ankh. Of per ankh, Ayi Kwei Armah has this to say:

“In its African origins the per ankh educational system, designed to take the young on a lifepath from ignorance into knowledge, was the venue for a home-based learning process. The institutional name, per ankh, specifically identified the venue of education as the home, the per. It also named the purpose of the best education: ankh, life. In effect, the purpose of education within the per ankh was to keep alive, for all future generations, the best values and knowledge, the best techniques and processes, in the history of the society” (The Way of Companions, 2018, p. 125)

The education that begins ‘at home’ is the education system where learners study as brothers and as sisters. They learn in a communal fashion, and this approach entails companionship, also having egalitarian aspects. The way it worked in the per ankh was that those individuals with a predilection for a particular aspect of learning will congregate and learn together. Let’s take for instance architecture, or engineering, or mathematics. Individuals would be brought together to study as companions at home. Bringing elitism and selectivity into the equation forces some to be privileged above others. The idea is that those who assume the positions of privilege then live off the sweat and toil of those under them. In the pyramid system of win-lose zero-sum dynamics, the gain of the privileged one equals the loss of the underprivileged. It is a system of finite thinking, where the underprivileged give away their energy, money, and in some cases their resources to support the privileged ones. Ayi Kwei Armah appears to argue against this system of inequity by providing us with an alternative model, an even more ancient one that existed for millennia before the elite system took over.

Tying it together… the main takeaway

For me, the main takeaway reading this book is that there is a viable alternative to social organization that was born and perfected by Africans in the pre-dynastic time of Ancient Kemet, which speaks more to the needs of all members of society as opposed to a privileged few. This system of thinking and being and in fact this culture or form of social organization, the Shemsw Maât, is offered as an alternative to the hierarchical or elite (pyramidal) form of social organization, It is in fact even older than the more mainstream version, the Shemsw Seth. The proponents of Shemsw Seth can be seen as the ‘takers’, the aristocrats or even plutocrats, the capitalists, the politicians and those who resort to war to become the elite. The alternative, the ‘socialists’, those who practice cooperation, reciprocity, philosophy, and widom follow the ways of Shemsw Maât.

Africans today must pay more attention to the Shemsw Maât way, because it is a way that is more inclusive and egalitarian, and that perhaps has the potential to bring more people up, instead of focusing primarily on only a few elite in society as the major beneficiaries. If the founding fathers of Black liberation had been aware of the mindset of Shemsw Maât, as opposed to just being aware of the Shemsw Seth forms of education they received, they may have taken the course of their Black liberation movements in directions that put African and African Diaspora priorities in the foreground in ways more reflective of African egalitarian culture. Therefore, Africans today, in seeking to re-educate themselves, should pay attention to and learn the ways of the Shemsw Maât, for it is a way that brought great culture and civilization to Black people.

As a final word, I would posit that my personal position would not be to choose either Shemsw Maât or Shemsw Seth but to embrace both. I say this for a number of reasons. The first is that the Shemsw Seth approach was powerful enough to arguably overthrow the Shemsw Maât approach in Kemet. The Shemsw Seth approach is also seen to be the approach of the colonizer. In order to be able to engage with and to manage the colonizer, it is important to know the ways of the warrior, and the politician. It is also however important to also incorporate the ways of wisdom, the way of the companions. Therefore, in order to balance things today, the Shemsw Maât approach is not only needed more in Africa today, given the historical prevalence of Shemsw Seth thinking since independence of African states, I think it is badly needed. Currently, the Shemsw Seth approach is running rampant in today’s post-colonial African governments. Few powerful checks and balances are in place.

If you would like to order Ayi Kwei Armah’s books to read, you may find them at Per Ankh books